MENTOR GRAPHICS v. EVE-USA, INC., SYNOPSYS EMULATION AND VERIFICATION S.A.S, SYNOPSYS, INC.

2015-1470, 2015-1554, 2015-1556

Appeals from the United States District Court for the District of Oregon

Decided: March 16, 2017

This lengthy opinion addresses: whether substantial evidence existed to support a jury’s infringement verdict; assignor estoppel; indefiniteness; eligible subject matter; preclusion of evidence of willful infringement and enhanced damages; written description; and claim preclusion.

[Editor’s note: The Court opinion is 42 pages, addresses 8 very different issues involving 6 patents – this case summary is roughly 2,000 words. Mentor asserted several patents against Synopsys, including U.S. Patent Nos.

6,240,376 (“the ’376 patent”)

6,947,882 (“the ’882 patent”)

6,009,531 (“the ’531 patent”)

5,649,176 (“the ’176 patent”)

Synopsys asserted two patents against Mentor—U.S. Patent Nos.

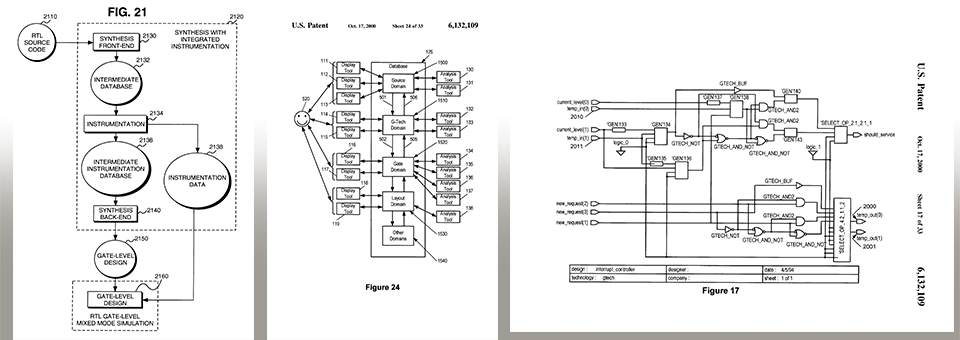

6,132,109 (“the ’109 patent”)

7,069,526 (“the ’526 patent”)]

BACKGROUND

The patents involve simulation/emulation technology. Two Mentor employees (and named inventors on the ‘376 Patent) left Mentor and founded EVE. Mentor sued EVE in 2006 for infringement of three patents. Mentor and EVE settled prior to trial, and EVE obtained a license to the three patents. The license contained a provision terminating the license upon acquisition of EVE by another company in the emulation industry.

Synopsys then acquired EVE, which terminated the license. Synopsys and EVE subsequently filed a declaratory judgment action, seeking a declaration that the three patents were invalid and not infringed. Mentor counterclaimed for willful infringement. Synopsys amended its complaint to assert claims of infringement of two Synopsys patents. The district court consolidated the suit with another suit involving a Mentor patent.

Only the ‘376 Patent was tried to verdict. The jury found in favor of Mentor and awarded damages of approximately $36,000,000.

Synopsys’ Appeal

Synopsys appeals the infringement verdict, the damages award, and the grant of summary judgment on the issue of assignor estoppel.

1. Infringement of Mentor’s ’376 Patent

Element b) of Claim 1 of the ‘376 Patent requires: synthesizing the source code into a gate-level netlist including at least one instrumentation signal, wherein the instrumentation signal is indicative of an execution status of the at least one statement. Synopsys argues it does not infringe because its emulators do not “indicate” an RTL statement but rather merely provide the name of a block of RTL that a developer can use to locate corresponding code.

Mentor’s expert testified that each probe signal shown in the waveform viewer identifies a portion of RTL by name, and the RTL name can be used to locate the corresponding source code. The Court discussed a portion of the expert’s testimony and found “substantial evidence to support the jury’s finding that the instrumentation signal indicates at least one RTL statement.”

2. Assignor Estoppel of Mentor’s ’376 Patent

Synopsys argued the Supreme Court “demolished the doctrinal underpinnings of assignor estoppel in the decision that abolished the comparable licensee estoppel in Lear, Inc. v. Adkins, 395 U.S. 653 (1969).” The Court disagreed, noting that in Diamond Scientific—a case decided after Lear– the continued vitality of the doctrine of assignor estoppel was acknowledged. See Diamond Sci. Co. v. Ambico, Inc., 848 F.2d 1220, 1222–26 (Fed. Cir. 1988).

3. Damages for Synopsys’ Infringement of Mentor’s ’376 Patent

Synopsys argued that the damage award should be vacated because the district court failed to apportion lost profits.

The Court stated that “compensatory damages under the patent statute, which calls for damages adequate to compensate the plaintiff for its loss due to the defendant’s infringement, should be treated no differently than the compensatory damages in other fields of law.” “The goal of lost profit damages is to place the patentee in the same position it would have occupied had there been no infringement…. lost profit patent damages are no different than breach of contract or general tort damages.”

A method to establish the patentee’s entitlement to lost profits is the Panduit test, which the Federal Circuit articulated in Rite- Hite Corp. v. Kelley Co., 56 F.3d 1538, 1545 (Fed. Cir. 1995) (en banc). “Damages under Panduit are not easy to prove.” The second Panduit factor requires a patentee to prove an absence of acceptable non-infringing alternatives. “Under this factor, if there is a non- infringing alternative which any given purchaser would have found acceptable and bought, then the patentee cannot obtain lost profits for that particular sale.”

Here, the relevant market contained two parties, Synopsys and Mentor, and one purchaser, Intel. This fact “makes this case quite narrow and unlike the complicated fact patterns that impact so many damages models in patent cases.”

Synopsys argued that a patentee must calculate the amount of profits it lost and then apportion its lost profits to cover only the patentee’s inventive contribution. The Court rejected this argument, applying a “but for” analysis: “but for” Synopsys’ infringement, Mentor would have made $36,417,661 in lost profits (which Synopsys did not dispute). The Court acknowledged that a different theory of “but for” damages might not adequately incorporate apportionment principles. However, “on the undisputed facts of this record, satisfaction of the Panduit factors satisfies principles of apportionment: Mentor’s damages are tied to the worth of its patented features.”

Synopsys argued that its emulators “out-perform Mentor’s in price, size, speed, and capacity.” Therefore, substantial evidence did not support the finding that Intel would have purchased Mentor’s emulators “but for” the infringement. However, Synopsys did not appeal any of the jury’s factual findings relating to damages. “[T]hus on appeal, it is left with a jury fact finding that Intel would not have bought Synopsys’ emulation system without the two infringing features, and Mentor would have made every single sale to Intel that Synopsys otherwise made.”

Synopsys and the amicus brief argue that not requiring an additional apportionment step after the Panduit test would “allow multiple entities to obtain lost profits on the same product where each entity holds a patent on a different ‘but for’ feature of the same product.” Under Panduit there can only be one recovery of lost profits for any particular sale, and Mentor had to prove no other supplier could have made those specific sales to Intel. “If there were any acceptable non-infringing alternative Intel would have purchased instead of Mentor’s emulator, then Mentor could not obtain lost profits.”

The Court acknowledged that the patented feature or features of a device must be the basis of the purchasing decision in order to obtain lost profits. The Court was satisfied, however, that the “jury found that if Synopsys had not infringed the Mentor patent by incorporating the two patented features into its emulators, Intel would not have purchased these products from Synopsys and would instead have purchased the emulators from Mentor — there were no non-infringing alternative emulators which would have satisfied Intel.“

4. Indefiniteness of Synopsys’ ’109 Patent

Read more: Federal Bar member attorneys may access the full case summary by Barnwell Whaley attorney Bill Killough in the April 2017 issue of Federal Circuit Case Digest. https://www.fedcirbar.org/IntegralSource/Case-Digest

Additionally, you may read the full opinion here.

B.C. “Bill” Killough is a registered patent attorney with Barnwell Whaley law firm with offices in Charleston, SC and Wilmington, NC. On behalf of his clients, Bill has obtained more than 275 United States patents, participated in prosecuting more than 100 foreign patent applications and he has filed more than 1000 trademark applications with the US Patent and Trademark Offices.